1st July marks the anniversary of the investiture of Prince Charles as Prince of Wales in Caernarfon Castle in 1969.

The event, though popular in Wales, was widely opposed by Welsh nationalists, for whom it symbolised England’s rights of conquest over Wales, and Wales’s lack of self-determination. Those who campaigned against the investiture included Dafydd Elis-Thomas, later leader of Plaid Cymru from 1984 to 1989, and Dafydd Iwan, chairman of Cymdeithas yr Iaith, whose song, ‘Carlo,’ satirised the event.

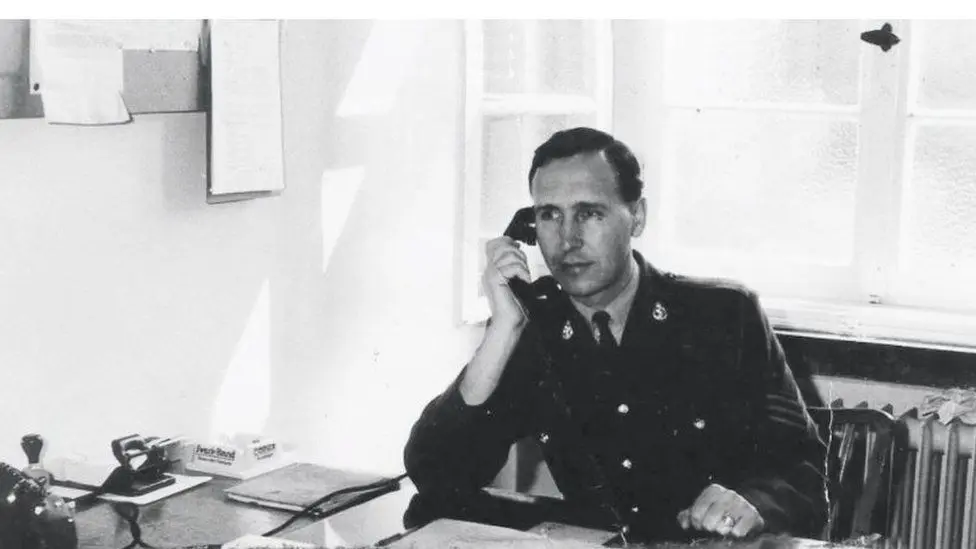

The investiture also ended Welsh nationalism’s brief experiment with armed revolt. The Free Wales Army’s plan to storm the castle with air support from the IRA was foiled when a letter outlining the plan was cunningly intercepted during transit through the Royal Mail, and its leaders, including Julian Cayo Evans and Dennis Coslett, were imprisoned for firearms offences on the day of the investiture. A number of bombs were placed by members of Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru with the intention of disrupting the ceremony, though only one, placed in a local policeman’s garden, went off as intended. Another exploded prematurely, killing two members of MAC, the so-called Abergele Martyrs. Their leader, John Barnard Jenkins, was arrested in November 1969, largely on the testimony of a fellow operative’s girlfriend, who was driven to a secret rendezvous on their way to a date.

John Jenkins subsequently claimed that as a non-commissioned officer in the British Army, he could have approached Prince Charles with a loaded firearm, had he wished, and could have found volunteers for a suicide mission, thus apparently discrediting any notion that MAC’s intention was to shed blood: the explosions were intended as a symbol of Welsh national resistance to English rule, just as the pomp that accompanied the investure was a symbol of the power of the British state. Even so, Gwynfor Evans remarks in his book, Fighting for Wales, that all attempts at armed revolt against English rule have failed, and that those movements which survived the 1960s were those that stayed close to the principles of pacifism and civil disobedience embraced by Plaid Cymru at its foundation, and while Ned Thomas dismisses the ‘pious lie’ that political violence is counterproductive, he condemns it nonetheless for the ‘moral corruption’ it brings to a moral movement.

In 2018 the Welsh government gave somewhat furtive consent to a plan to rename the second Severn crossing as the Prince of Wales Bridge to commemorate the investiture. Despite widespread opposition to what still seemed a slur, and a petition which was signed by 30,000 people in a country of just 3 million, a subdued ceremony was attended by the prince on 2nd July 2018, with little advanced publicity and few invitations to the press. What the British state once did openly by popular consent it continues to do by stealth in the face of democratic opposition, incapable of imagining any way to treat us, it seems, but as an obedient ‘principality’ in their failing yet belligerent English empire: an empire bitterly divided, yet screaming its unity, fearful of the future, yet boastful of the past, rushing in an unreasoning fury towards the means of its dissolution.