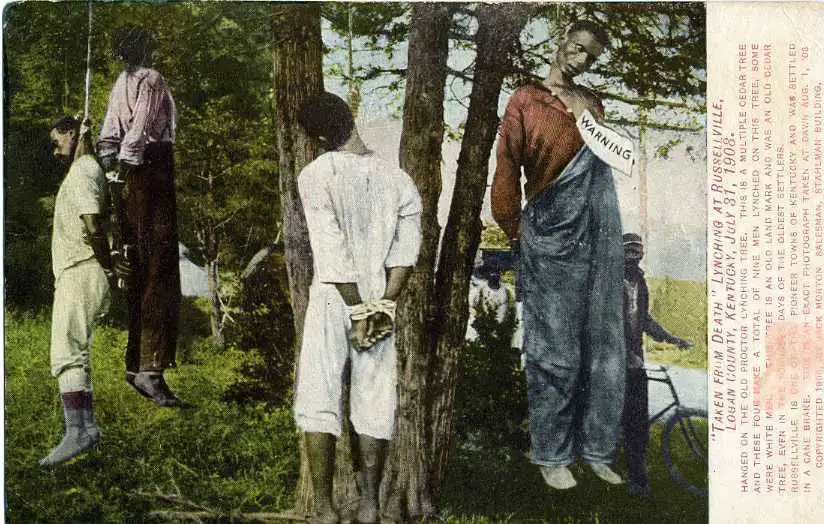

‘Even the Nazis did not stoop to selling souvenirs of Auschwitz, but lynching scenes became a burgeoning subdepartment of the postcard industry. By 1908, the trade had grown so large, and the practice of sending postcards featuring the victims of mob murderers had become so repugnant, that the U.S. Postmaster General banned the cards from the mails.’ –Richard Lacayo, ‘Blood at the Root.’ Time, 2nd April 2000.

The following is an eye-witness account of the lynching of a black man, Henry Smith, suspected of killing a police officer’s child. It took place in 1899:

‘At twelve o'clock [his] train was met by a surging mass of humanity 10,000 strong. The Negro was placed upon a carnival float in mockery of a king upon a throne, and, followed by an immense crowd, was escorted through the city (Paris, Texas) so that all might see the most inhuman monster known in current history... His clothes were torn off piecemeal and scattered in the crowd, people catching the threads and putting them away as mementos. The child’s father, her brother, and two uncles then gathered about the Negro as he lay fastened to the torture platform and thrust hot irons into his quivering flesh. It was horrible — the man dying by slow torture in the midst of smoke from his own burning body. Every groan from the fiend, every contortion of his body was cheered by the thickly packed crowd of 10,000 persons, the mass being 600 yards in diameter, the scaffold being the centre. After burning the feet and legs, the hot irons — plenty of fresh ones being at hand — were rolled up and down Smith’s stomach, back and arms. Then the eyes were burned out and irons thrust down his throat.’

Another lynching of a black man suspected of murder is described in a newspaper article, and also took place in 1899. In this case, the cooked flesh of the victim was consumed by participants and witnesses of the auto da fé:

‘In the presence of nearly 2000 people, who sent aloft yells of defiance and shouts of joy, Sam Holt was burned at the stake on a public road. Before the torch was applied to the pyre, the Negro was deprived of his ears, fingers, and other portion of his body with surprising fortitude. Before the body was cool, it was cut to pieces, the bones were crushed into small bits and even the tree upon which the wretch met his fate was torn up and disposed of as souvenirs. The Negro’s heart was cut in small pieces, as was also his liver. Those unable to obtain the ghastly relics directly paid more fortunate possessors extravagant sums for them. Small pieces of bone went for 25 cents, and a bit of liver, crisply cooked, for 10 cents.’

When those who had been burnt to death were subsequently part eaten, the lynchings were described as ‘barbecues’ and remembered fondly for their carnival and community atmosphere by those who participated. The following account, by a NAACP official, describes the effect of participating in such events on children:

‘[In Florida one morning,] I walked along the road which led from a beautiful little town to the spot where five Negros had been burned [a few years before]. Three shining-eyed, healthy, cleanly children, headed for school, approached me. As I neared them, the eldest, a ruddy-cheeked girl of nine or ten, asked if I was going to the place where “the niggers” had been killed. I told her I might stop and see the spot. Animatedly, almost joyously as though the memory were of Christmas morning or the circus, she told me — of “the fun we had burning the niggers.”’

These accounts are quoted in the second chapter of Orlando Patterson’s book, Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two American Centuries (1998). Among the other practices it describes is the commonplace crucifixion of rebellious slaves by Christian slaveowners, and the ritualisation and commercialisation of torture and execution. Its thesis is that the racist after-effects of slavery persist in America at the end of the 20th Century. And it seems that two decades into the 21st Century, amidst the hatred and fear promoted by Nigel Farage, Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán and others like them, the rise of fascism in countries that boasted of their liberalism, we are still finding black men hanging from trees.